Cognitive Work of Hypothesis Exploration during Anomaly Response

This week we’re back with another article from the acm queue November/December issue on human factors. This time with Marisa Grayson examining the incident response in software. If haven’t read her thesis, I strongly recommend it, and this article is a nice preview of some of her work.

She also focuses directly on software, so the learnings are directly applicable to us. In the article, she uses Cognitive Systems Engineering to analyze two incidents, both that probably sound familiar. They’re primarily focused on what happens above the line.

Grayson reminds us early on that:

“It seems easy to back at incident and determine what went wrong. The difficulty is understanding what actually happened now to learn from it.”

This is because hindsight bias can cause us to look back and see an oversimplified explanation that doesn’t fit the reality of the way the situation unfolded. When we look backwards, with all the knowledge available to us, already knowing the outcome, it can be tempting to draw a straight line through events. But that’s not how it unfolded, so understanding how hypothesis are explored, especially during an incident can be extremely helpful.

Also, understanding the cognitive work can help us design and evaluate tools that we build to help responders.

“High-reliability continuous development and deployment pressures engineers to keep pace with change and adapt to constant challenges. Their hypothesis exploration should be supported by the tools they use every day because they are already solving problems that end users never even know about.”

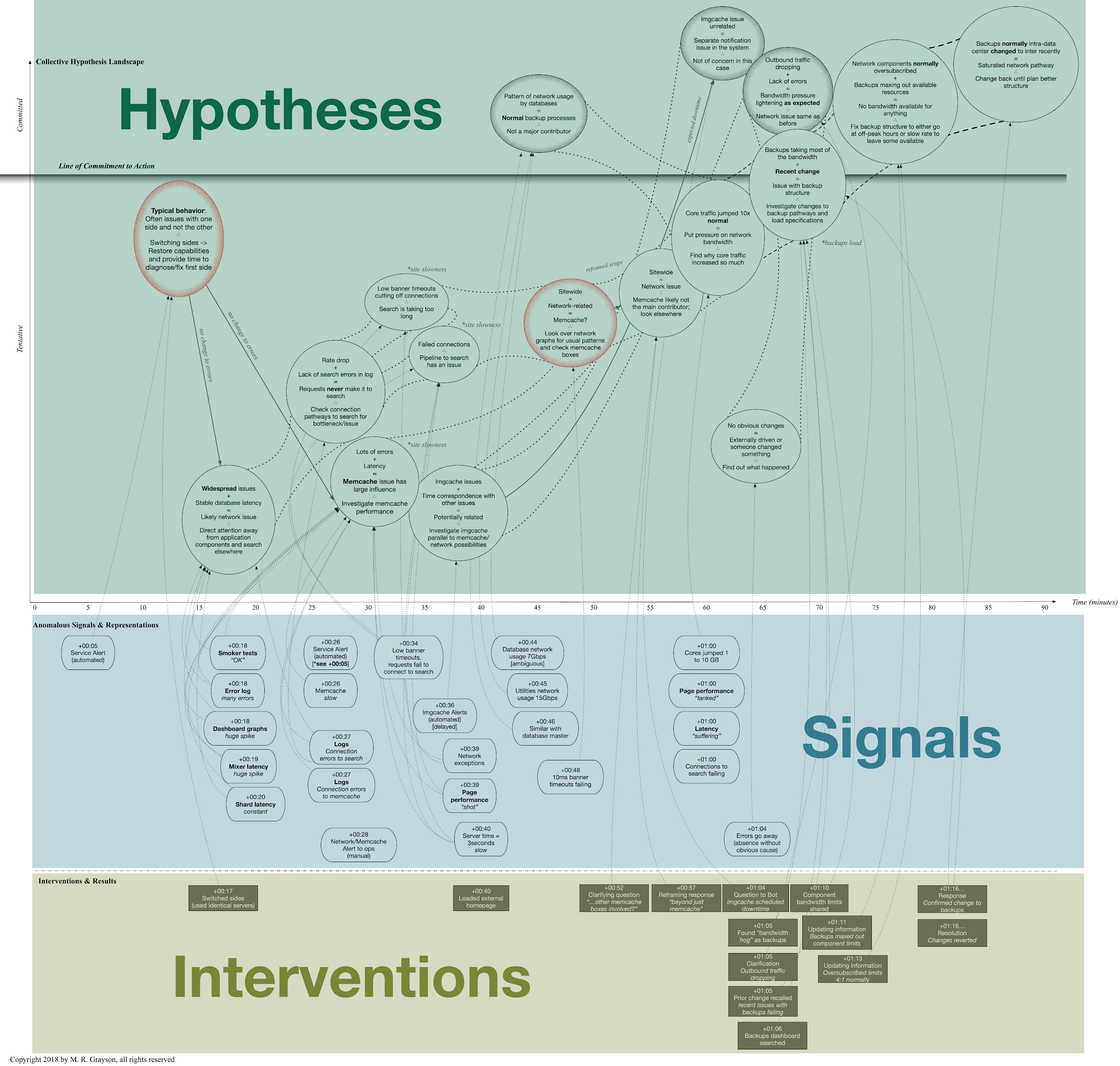

Grayson has created some diagrams for the case studies that are featured. They are based off of the chat logs gathered during the incident. Not only do they help represent the complexity of the response, but they also show some of the parts, such as the signals and representations and the interventions.

The diagram helps us understand that hypotheses continue to be generated, it is not something that just happens once and then the next step is moved on to. We see that some signals help inspire new ideas, whereas others may cause the hypothesis to be dismissed.

All of these sections are stacked on top of each layer comes from the lower. The hypothesis space were generated based on signals, some of which resulted from the interventions.

The number of different paths of hypotheses and signals and interventions shows that there are a number of ways in which responders can be overloaded as well as showing the complexity of the system and the need for more information in investigating that complexity.

It’s hard to get a sense of just reading about the cases or even looking at the diagram, but they’re taking place over time. Sitting reading about it, that might sound obvious, but can’t be overlooked. Time affects the investigation. A bias towards investigating more recent changes to the system, but also time pressure that can influence the investigation.

In the first case that is featured ideas converged down to one with a some certainty, whereas the second had many diverging paths. In both cases you could say the initial response was “unsuccessful” but that initial response was needed in order to get to the information required to ultimately overcome the issue.

This hints at a mindset that I’ve seen in both good SRE and medical teams (and even sometimes poker players), the ability to see the result of an action while with holding blame or judgement about it. In this case the ability to apply the label “unsuccessful” to the action without applying it to the team, responder, or overall response.

Takeaways

- Hypothesis exploration is a continuous, ongoing process, not something that just happens once and is done.

- Hindsight bias can cause us to come up overly simple explanations that don’t match the reality of what occurred.

- Understanding the cognitive work of responding to an incident and understanding what’s going on can help with creating or evaluating tools.

- Hypotheses are created and adjusted based on signals and the results of interventions.

- This area, the hypotheses space, is focused on what happens above the line or representation.

- Time shapes investigations, both as pressure and influences what changes or events are likely to be examined first.

Subscribe to Resilience Roundup

Subscribe to the newsletter.